Introduction to Adaptive Experimentation

In engineering tasks we often encounter so-called "black box" optimization problems, situations where the relationship between inputs and outputs of a system is not known in advance. In these scenarios practitioners must tune parameters using many time- and/or resource-consuming trials. For example:

- Machine learning engineers and researchers may have neural network architectures and training procedures that may depend on numerical hyperparameters, such as learning rate, number of embedding layers or widths, data weights, data augmentation choices, etc. One often seeks to understand and/or optimize with respect to these tradeoffs .

- Materials scientists may seek to find the composition and heat treatment parameters that maximize strength for an alloy.

- Chemists may seek to find the synthesis path for a molecule that is likely to be a good drug candidate for a disease.

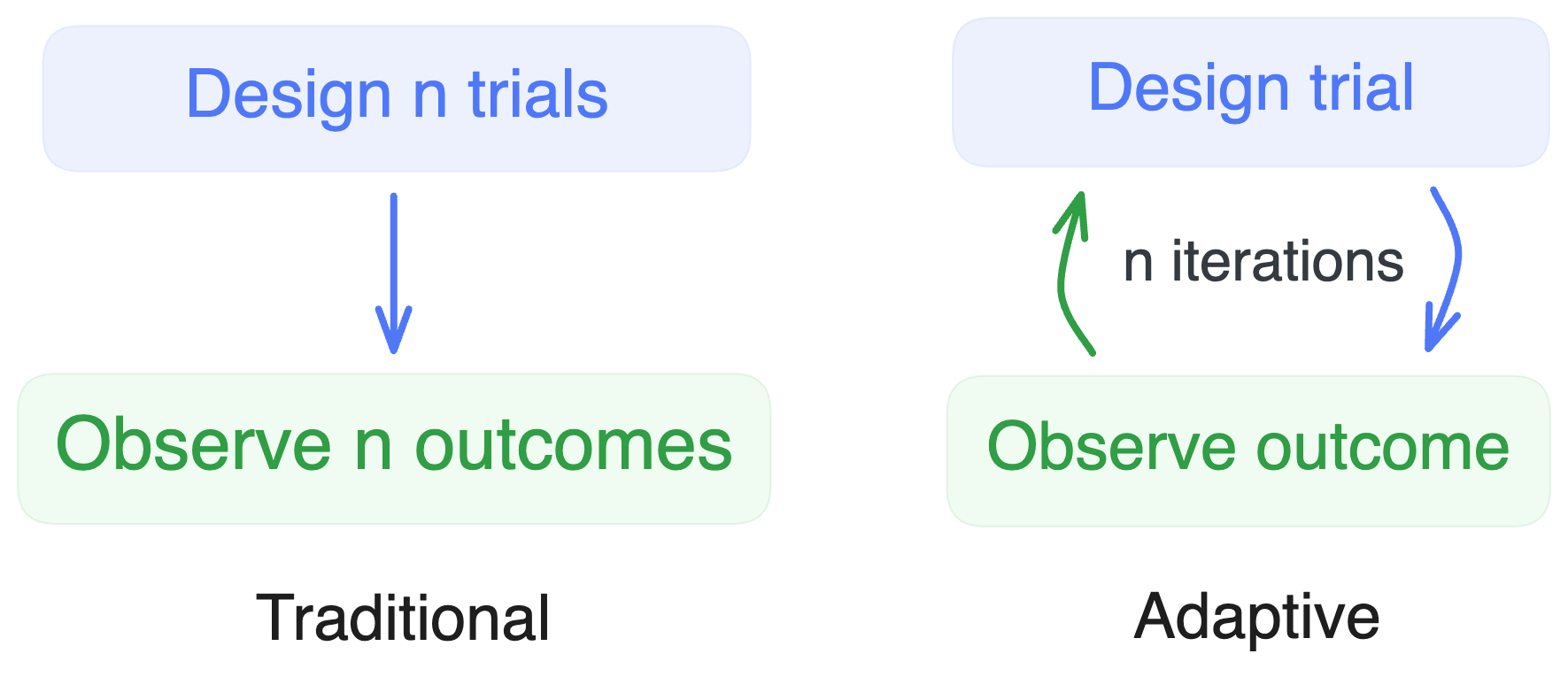

Adaptive experimentation is an approach to solving these problems efficiently by actively proposing new trials to run as additional data is received. Adaptive experimentation is able to explore large configuration spaces with limited resources through the use of specialized models and optimization algorithms.

The basic adaptive experimentation flow works as follows:

- Configure your optimization experiment, defining the space of values to search over, objective(s), constraints, etc.

- Suggest new trials, to be evaluated one at a time or in a parallel (a “batch”)

- Evaluate the suggested trials by executing the black box function and reporting the results back to the optimization algorithm

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until a stopping condition is met or the evaluation budget is exhausted

Bayesian optimization, one of the most effective forms of adaptive experimentation, intelligently balances tradeoffs between exploration (learning how new parameterizations perform) and exploitation (refining parameterizations previously observed to be good). To achieve this, Bayesian optimization utilizes a surrogate model (most commonly, a Gaussian process) to predict the behavior of the “black box” at any given input configuration (parameterization, whatever we want to call it). An acquisition function utilizes predictions from this model to identify new parameterizations to identify promising candidates to evaluate.